Key Takeaways

When it comes to fighting games, not many are as iconic as Mortal Kombat. The series, which got its start in 1992, has maintained a prominent presence for decades. You’d be hardpressed to find a gamer that doesn’t know where the phrase “Finish him!” comes from. But do you know the story of how Mortal Kombat came into existence?

The Van Damme Game That Never Was

Picture Midway Games in 1991. Capcom’s Street Fighter II has set arcades on fire, and companies everywhere want their own fighting game hit. Midway approaches programmer Ed Boon and artist John Tobias with a project: create a game starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, the martial arts action star. The title would be Universal Soldier, tied to Van Damme’s upcoming film.

The deal falls through. Van Damme is in negotiations with another company for a game that never materializes. Some sources indicate he was already negotiating elsewhere, or that the deal simply couldn’t come together.

Most companies would kill the project. Midway does something different.

Boon and Tobias pitch their own concept: a fighting game darker and more realistic than Street Fighter, inspired by martial arts films like Enter the Dragon and Bloodsport. The vision includes digitized actors instead of hand-drawn sprites. Management gives them 10 months and roughly $1 million. The team: Boon on programming, Tobias and John Vogel on art, Dan Forden on sound.

Van Damme’s ghost remains in the final game. Johnny Cage shares his initials (JC), performs a signature splits punch to the groin, and plays a narcissistic Hollywood action star. The character is a deliberate parody of the whole situation.

Years later, Boon explained their approach: they wanted something “a lot more hard edge, a little bit more serious, a little bit more like Enter the Dragon or Bloodsport” than the cartoonish fighters dominating arcades.

Four People, Ten Months, One Camera

The development of Mortal Kombat happened at breakneck speed with minimal resources. Tobias owned a Hi-8 camcorder—consumer-grade video equipment. The team filmed local martial artists performing moves in a backroom at Midway’s offices. No professional studio, no motion capture rig, not even proper mats for actors to safely perform falls.

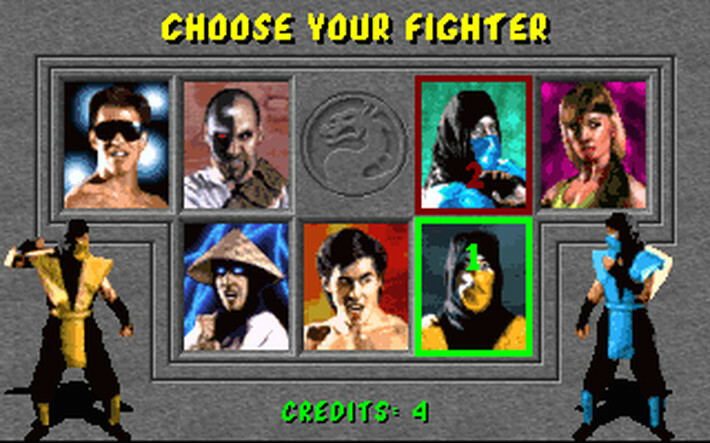

The cast consisted of martial artists from the Chicago area. Daniel Pesina played Johnny Cage and all three ninja characters (Scorpion, Sub-Zero, and secret fighter Reptile). Ho-Sung Pak portrayed Liu Kang and the elderly version of antagonist Shang Tsung. Elizabeth Malecki became Sonya Blade. Richard Divizio played Kano. Carlos Pesina served as Raiden.

The boss character Goro presented a unique challenge. The four-armed Shokan warrior couldn’t be filmed with an actor. Instead, Curt Chiarelli created a stop-motion model that was photographed frame by frame.

Technical specs paint the picture: eight megabytes of graphics data, each character rendered with 64 colors across roughly 300 frames of animation. Tobias’s consumer camcorder captured everything.

The development process allowed for spontaneous creativity. Scorpion’s iconic spear move—the one where he yells “Get over here!” and drags opponents toward him—was conceived during filming. Boon suggested it on the spot, the actor performed it, and Boon recorded his own voice for the catchphrase right there. The entire sequence took minutes from concept to capture.

That spontaneity became a signature. Boon has voiced Scorpion’s “Get over here!” in every Mortal Kombat game since 1992. The Guinness Book of World Records recognized him in 2010 as the “longest-serving video game voice actor” for this single role spanning nearly three decades.

The team struggled with the game’s name. For six months, nobody could agree on anything. Suggested titles included Kumite, Dragon Attack, Death Blow, and Fatality. Pinball designer Steve Ritchie sat in Boon’s office one day and saw someone had written “Kombat” on the whiteboard—the C crossed out and replaced with a K, just to be different. Ritchie asked, “Why don’t you name it Mortal Kombat?” The name stuck.

That deliberate misspelling became a franchise trademark. The developers now intentionally replace hard C sounds with K throughout the series—though Boon notes they usually spell words correctly during development and only make the substitution when someone suggests it.

October 8, 1992: Arcade Lightning

Mortal Kombat first appeared in Chicago arcades in April 1992 as a location test. The build included only six characters—all male. When the test version became popular within Midway’s offices, management gave the team more time. They added Sonya Blade to the roster, bringing the count to seven playable fighters.

The official arcade release happened October 8, 1992. The cabinet initially shipped in plain white with a handwritten “MORTAL KOMBAT” sticker. The game itself stood out.

Where Street Fighter II presented colorful, anime-style characters, Mortal Kombat offered photorealistic fighters filmed in live action. This wasn’t entirely new—Midway’s own N.A.R.C. and Atari’s Pit-Fighter had used digitized sprites earlier—but no fighting game had combined the technique with such brutal content.

The violence was the hook. Every punch and kick splattered blood. Fighters left crimson pools on the ground. And if you won two rounds and knew the secret button combination, you could perform a Fatality: a finishing move that killed your defeated opponent in spectacular fashion.

Sub-Zero ripped out spines. Scorpion incinerated foes with fire breath. Kano tore out beating hearts. Johnny Cage punched heads clean off. The moves were preposterous, gory, and completely unlike anything in arcades at the time.

The “dizzied” mechanic from earlier fighting games inspired Fatalities. Boon hated getting dizzied mid-match—it felt frustrating to lose control of your character while vulnerable. Tobias and Boon realized they could eliminate that frustration by moving the mechanic to after the match ended, when the outcome was already decided. Instead of a dizzy opponent taking a few free hits, the loser would die spectacularly.

RePlay magazine reported Mortal Kombat as the second most popular upright arcade cabinet in September 1992. By October it topped the charts, holding the number one spot through November, then again from February to March 1993, and once more in November 1993. The game generated over $300,000 from arcade cabinets in 1993 alone—unprecedented numbers.

Tobias later admitted the ultraviolent content hadn’t been planned from the start. The gore was implemented gradually as development progressed, with each team member trying to outdo the last. Boon and Tobias, working in tight collaboration with quick iteration times, kept raising the stakes on each other. As Tobias noted, they could “literally prototype up any idea in minutes” without relying on anyone else.

Players discovered secrets beyond the violence. Reptile, a green-clad ninja, appeared as a hidden character. Boon added Reptile late in development—finishing the character in a single night and shipping him in the third arcade revision. The addition was so secret that even Tobias didn’t know about it until the character was already in arcades. This annoyed Tobias, who insisted that Mortal Kombat II development would require everyone to be aware of hidden content. (Boon would still manage to sneak in Noob Saibot anyway.)

Mortal Monday and the Blood Code Wars

Acclaim Entertainment licensed Mortal Kombat for home consoles in 1993. The simultaneous release of four versions—Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, Game Boy, and Game Gear—happened September 13, 1993. Marketing dubbed it “Mortal Monday.”

The campaign was massive. Multi-million dollar promotion included prime-time TV commercials, print advertising, and giveaways all building to a single release date across four platforms. The advertising itself drew attention. One Sega commercial showed a boy gaining his friends’ respect after winning at Mortal Kombat, then angrily knocking over a cookie tray while roaring “I said I wanted chocolate chip!” Senator Joe Lieberman would later cite this ad as promoting violence.

The home versions faced different fates based on their publishers’ approaches.

Nintendo maintained strict content guidelines in 1993. They refused to allow the arcade game’s gore on their system. Acclaim complied, censoring Mortal Kombat for the SNES and Game Boy. Blood became sweat (green instead of red on SNES). Fatalities were modified to remove gore—Sub-Zero’s decapitation became a freeze-and-shatter move, Johnny Cage’s head-punch became a shadow kick through the chest, and Raiden’s electrocution reduced opponents to dust.

Sega took a different approach. The Genesis and Game Gear versions shipped with the gore toned down to meet Sega’s MA-13 rating. The blood and fatalities existed in the code. Players who entered the Blood Code—A, B, A, C, A, B, B (which spells “ABACABB,” a reference to the band Genesis)—unlocked the full arcade violence, bumping the rating to MA-17.

The result: Sega’s version outsold Nintendo’s heavily. GamePro declared the Genesis port superior despite less responsive controls, because “Mode A” with the blood code activated made it “a beat-em-up force.” The SNES version’s cleaner graphics and better sound couldn’t overcome the fact that it was censored.

Gregory Fischbach, Acclaim’s chief executive, later told the BBC: “To my mind, Mortal Kombat was comic book violence, but some people got upset about it. People looked at it as though we were selling it to nine-year-old children.” Nintendo’s demand to change the blood color was, he said, “pretty stupid.”

The censorship battle revealed a fundamental tension: parents and politicians who didn’t understand gaming, versus publishers trying to navigate moral panic while maximizing sales.

Capitol Hill vs. Sub-Zero

Joe Lieberman’s chief of staff approached the Senator in 1993 with concerns about Mortal Kombat’s violence. Lieberman reviewed the Genesis version and decided the game’s realistic graphics combined with graphic content created a problem requiring government intervention.

On December 9, 1993, Senators Lieberman and Herb Kohl led Congressional hearings on video game violence. They showed footage from Mortal Kombat and Night Trap—another game using digitized actors—to make their case. Professor Eugene F. Provenzo testified as an expert, claiming such games “have almost TV-quality graphics [but] are overwhelmingly violent, sexist and racist.”

The hearings put Nintendo and Sega in direct conflict. Howard Lincoln, Nintendo of America’s vice president, testified that Nintendo had maintained family-friendly standards by censoring Mortal Kombat. He implicitly criticized Sega for allowing the gore via the blood code. Sega defended consumer choice.

Lieberman argued that without regulation, violent games would poison children’s development. He stated: “Instead of enriching a child’s mind, these games teach a child to enjoy torture,” before showing footage of Sub-Zero’s spine rip.

The videogame industry faced a choice: self-regulate or face government-mandated ratings. The Interactive Digital Software Association (later renamed the Entertainment Software Association) chose self-regulation. They formed the Entertainment Software Rating Board in 1994.

The ESRB launched with five ratings: Early Childhood, Kids to Adults, Teen, Mature, and Adults Only. Mortal Kombat received an M for Mature when officially rated, making it one of the first games to bear the label that would become synonymous with the franchise.

The hearings’ outcome was mixed. Congress chose not to impose federal regulations, satisfied with the industry’s self-regulatory approach. The ESRB remains voluntary—no legal consequences exist for selling M-rated games to minors, though most retailers adopted policies aligned with the ratings.

Boon later reflected on the controversy with surprising sympathy. In 2010 he admitted: “I wouldn’t want my ten-year-old kid playing a game like that.” The creator understood the concern even as he benefited from the attention.

The moral panic paradoxically boosted sales. Everyone wanted to play the game that troubled senators. The controversy gave Mortal Kombat free publicity worth millions. By 1994, Mortal Kombat games had sold over 6 million units. The figure would reach 26 million by 2007, 30 million by 2012, 79 million by 2022, and surpass 100 million by 2025.

For better or worse, Mortal Kombat changed how society viewed video games. The medium was no longer just for children. Games could target mature audiences, provoke genuine controversy, and become cultural phenomena precisely because they pushed boundaries.

Mortal Kombat II: Bigger, Bloodier, Better

Success demanded a sequel. Mortal Kombat II hit arcades April 1993—just six months after the original. The speed was remarkable considering the leap in quality.

WMS Industries, Midway’s parent company, reported revenue jumping from $86 million to $101 million in the quarter ending December 31, 1993, with much of the gain attributed to MKII arcade sales. The game had “unprecedented opening week sales figures never seen before in the video game industry,” beating summer blockbuster films at the box office for the first time.

The development team upgraded everything. Instead of Tobias’s $200 Hi-8 camcorder, they used a broadcast-quality Sony camera costing $20,000. Actors were lightly sprayed with water for a sweaty, glistening appearance. Post-editing enhanced flesh tones and muscle definition, setting the game apart from other digitized fighters.

Near the end of development, the team switched to blue screen techniques and processed footage directly into computers for simpler workflow. The visual improvement was dramatic.

The roster expanded from 7 to 12 playable characters. Liu Kang, Johnny Cage, Raiden, Scorpion, Sub-Zero, and Reptile returned. Shang Tsung, previously the boss, became playable with his shapeshifting abilities intact. New fighters included Kitana, Mileena, Kung Lao, Jax, and Baraka. Two hidden characters—Smoke and Noob Saibot (Ed Boon and John Tobias’s surnames spelled backward)—appeared for players who met special conditions.

Kintaro replaced Goro as sub-boss. Shao Kahn, the emperor of Outworld, served as final boss. Both moved faster and hit harder than playable characters, with different rules governing their abilities.

Gameplay refinements made combat smoother and more responsive. Controls felt precise. Special moves flowed naturally into high-damage combos. The game introduced multiple finishing moves per character—two Fatalities each, plus Friendships (silly, non-violent gestures) and Babalities (turning opponents into crying infants). Stage Fatalities appeared in The Dead Pool, Kombat Tomb, and Pit II stages.

The additions showcased the series’ dark humor. After performing a Mercy—restoring a small amount of the opponent’s health—players could execute an Animality, transforming into an animal to kill the opponent. Kung Lao baked cakes, Reptile advertised dolls, Liu Kang danced with a disco ball. The Friendship moves reminded players that beneath the gore, Mortal Kombat didn’t take itself too seriously.

Background details rewarded close observation. Ed Boon’s face appeared superimposed on trees in the Living Forest stage. Dan Forden, the sound designer, would occasionally pop up in the corner of the screen after an uppercut to yell “Toasty!”—originally planned as “You’re Toast!” before evolving during development.

Home versions shipped across 1993-1995 for nearly every platform: Genesis, SNES, Game Boy, Game Gear, MS-DOS, Amiga, 32X, Saturn, and PlayStation. This time Nintendo allowed the full gore on SNES. Having lost market share to Sega’s uncensored Genesis version of MK1, Nintendo couldn’t afford another sanitized release.

The SNES port by Sculptured Software received praise for its accuracy to the arcade. Sprites appeared smaller due to hardware limitations and some speech was missing, but the game felt remarkably close to its source. A secret team battle mode accessed via code let both players choose 8 characters to fight in succession—the genesis of the endurance matches that would become series staples.

Critics and fans often call MKII the best in the series. The game took everything that worked in the original, fixed what didn’t, and expanded content dramatically without diluting the experience. The core appeal remained: visceral combat with over-the-top finishing moves, now with twice the characters, secrets, and gore.

The Run Button Revolution: MK3

Mortal Kombat 3 arrived in arcades April 1995, accompanied by what the Guinness World Records dubbed the “largest promotional campaign for a video game” at the time. Sony Computer Entertainment paid Midway $12 million for exclusive worldwide rights to the 32-bit PlayStation version through the first quarter of 1996, demonstrating how valuable the franchise had become.

The third installment abandoned the tournament structure of its predecessors. This time, Shao Kahn resurrected his bride Sindel and invaded Earthrealm directly. The storyline justified wholesale changes to the roster: only five characters from MKII returned (Liu Kang, Sonya Blade, Sub-Zero, Shang Tsung, and Kung Lao). Seven new fighters joined, including cyborg ninjas Cyrax, Sektor, and Smoke (no longer a hidden character), plus Sheeva, Sindel, Kabal, Stryker, Nightwolf, and Jax. Kano and Johnny Cage—in the original game—were absent. The Graveyard stage included a tombstone reading “Cage,” indicating Johnny’s death.

The development team considered switching to 3D graphics but decided to stick with digitized sprites for one more generation. The graphical style remained consistent with MKII, though many felt MK3’s aesthetics looked less cohesive than its predecessor.

The major gameplay innovation: a Run button and corresponding Run meter. This addressed player feedback that previous games gave too much advantage to defensive players. Now fighters could dash toward opponents, applying pressure and setting up aggressive offense. Holding the Run button depleted a meter that refilled when released. The mechanic fundamentally changed the pace of matches.

Combos evolved from MKII’s simple chains into predefined sequences with specific timing. Players could string together multiple hits for devastating damage. The combo system added strategic depth while maintaining accessibility—button mashers could still win against unskilled opponents, but dedicated players found new layers to master.

Animalities returned from MKII, requiring players to first perform a Mercy before executing the transformation-based Fatality. Three new Stage Fatalities appeared in the Subway, Bell Tower, and Pit 3 arenas.

The game introduced Kombat Kodes—six-symbol codes entered at the versus screen in two-player matches. Each player entered three symbols using high punch, high kick, and low kick buttons. The codes modified gameplay (no power bars, unlimited run, fast uppercut recovery), fought hidden characters (Smoke, Noob Saibot), or displayed messages. Examples: 460-460 enabled Randper Kombat (random characters assigned), 688-422 activated Dark Kombat (fights in near darkness), 642-468 launched the Galaga mini-game.

The Ultimate Kombat Kode went further—a 10-character sequence entered on the game over screen that could permanently unlock hidden content like playable Smoke. Enter the symbols correctly and hear Shao Kahn say “Outstanding,” confirming success.

Home versions hit October 13, 1995—dubbed “Mortal Friday”—though not all platforms made the date. Williams Entertainment handled publishing for North America instead of Acclaim (who published previous titles). The Game Gear version never released in North America at all.

The Game Boy port cut content drastically: only 9 of 15 fighters, 5 stages, no button-link combos, and only Fatalities and Babalities as finishers. Despite severe limitations, the graphics quality impressed for the hardware.

Reception was positive though not as universally beloved as MKII. Critics appreciated the Run button and Kombat Kodes but some felt the game lacked the predecessor’s cohesion. The roster shake-up alienated players attached to missing favorites.

Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3, released later in 1995, added characters back (including masked Reptile, Ermac, and Klassic Sub-Zero) and became the definitive version. Mortal Kombat Trilogy (1996) for PlayStation, Saturn, Nintendo 64, and PC included nearly every character from the first three games, with all bosses playable—Goro, Kintaro, Motaro, and Shao Kahn.

The Graveyard stage in MK3 contained Easter eggs: tombstones bearing the last names of the design team (Ed Boon, John Tobias, Dan Forden, John Vogel, Tony Goskie, Dave Michicich), each with birthdates and a shared death date of April 1, 1995—the arcade release day.

Legacy: How MK Changed Gaming Forever

Mortal Kombat’s impact extends far beyond sales figures and controversy.

The ESRB’s Creation

Most directly, the franchise catalyzed the Entertainment Software Rating Board’s formation. Before 1993, games had no age ratings. Arcades were still popular and console graphics remained rudimentary enough that realistic depictions of violence or sexual content rarely appeared in homes. Mortal Kombat changed that calculation.

The ESRB structure established in 1994 remains largely intact 30 years later. Ratings range from Early Childhood to Adults Only. Content descriptors inform parents about specific elements (Blood and Gore, Intense Violence, Strong Language). The system is voluntary but nearly universal—major retailers refuse to stock unrated games, and console manufacturers won’t license games without ESRB ratings.

The board’s creation had unintended consequences. By analyzing and rating violent content without banning it, the ESRB effectively legitimized mature games. Critics could no longer argue such content had no place in gaming when an official ratings board assessed it, assigned an appropriate age restriction, and displayed that rating prominently on packaging.

Ed Boon reflected on this irony in 2010. While he admitted he wouldn’t want his own ten-year-old playing Mortal Kombat, he also recognized the ratings system protected creative freedom. Games could target adults without interference, much like R-rated films.

Fighting Game Innovation

Within its genre, Mortal Kombat codified several mechanics that became standards:

The block button replaced Street Fighter’s hold-back-to-block. This freed players to move backward without defending, adding offensive options.

Juggling and air combos expanded combo potential beyond ground attacks. Launch opponents into the air, follow with additional hits before they land.

Secret characters hidden through specific conditions (fight Reptile by winning a double-flawless victory on the Pit stage without blocking, during a silhouette flying past the moon). Players shared discoveries organically, creating community around secrets.

The palette-swap technique for creating “new” characters (Scorpion, Sub-Zero, and Reptile shared sprites but played differently). This maximized content from limited resources while giving each fighter distinct identities.

Digitized Graphics Era

While not the first to use digitized actors (Pit-Fighter and N.A.R.C. preceded it), Mortal Kombat popularized the technique for fighting games. This sparked a wave of imitators through the mid-1990s: Bio F.R.E.A.K.S., BloodStorm, Killer Instinct, Primal Rage, Way of the Warrior, Midway’s own War Gods.

Most clones failed. Tobias commented on the copycat products: “Some of the copycat products back then kind of came and went because, on the surface level, the violence will attract some attention, but if there’s not much to the product behind it, you’re not going to last very long.”

The technique fell out of favor as 3D graphics matured. Textured 3D models offered more flexibility and better aging. Mortal Kombat 4 (1997) became the series’ first 3D entry, abandoning digitization for motion capture and polygonal models.

Cultural Phenomenon

Mortal Kombat transcended gaming to become a multimedia franchise. The 1995 Paul W.S. Anderson film earned $122 million worldwide on a $18 million budget, making it the highest-grossing video game adaptation at the time. A sequel (Mortal Kombat: Annihilation, 1997) performed poorly critically and commercially.

The franchise spawned comic books, an animated series (Mortal Kombat: Defenders of the Realm, 1996), a live tour, toy lines, and a card game. In 2021, a new film reboot continued Hollywood’s relationship with the property.

The 2011 video game series reboot returned the franchise to cultural prominence. Mortal Kombat (2011), Mortal Kombat X (2015), and Mortal Kombat 11 (2019) each received critical acclaim and strong sales. Mortal Kombat 1 (2023) continues the series.

The “K” Legacy

That deliberate misspelling—Kombat with a K—became iconic. The series intentionally substitutes K for hard C sounds throughout: Kombat Kodes, Klassic characters, Mortal Kombat Komplete Edition. The affectation started as a simple differentiator and became a brand identifier.

What made Mortal Kombat different from Street Fighter II?

Mortal Kombat used digitized actors instead of hand-drawn sprites, creating a photorealistic look. The block button replaced hold-back-to-block mechanics. Fatality finishing moves allowed players to kill opponents with gory sequences. The combination of realistic graphics and extreme violence set it apart.

Who were the original Mortal Kombat actors?

Daniel Pesina played Johnny Cage and all three ninjas (Scorpion, Sub-Zero, Reptile). Ho-Sung Pak portrayed Liu Kang and Shang Tsung. Elizabeth Malecki was Sonya Blade. Richard Divizio played Kano. Carlos Pesina portrayed Raiden. Goro was a stop-motion model created by Curt Chiarelli rather than an actor.

Did Mortal Kombat create the ESRB?

Yes (in a way). The game’s graphic violence led to U.S. Congressional hearings in December 1993. Senators Joe Lieberman and Herb Kohl showed footage of Mortal Kombat and Night Trap to argue for government regulation of video games. The industry responded by creating the Entertainment Software Rating Board in 1994 to self-regulate content.

What was “Mortal Monday”?

September 13, 1993—the simultaneous release date for Mortal Kombat on four home platforms (Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, Game Boy, Game Gear). Acclaim Entertainment launched a massive multimedia marketing campaign building to this single release day.

What was the Blood Code?

The Sega Genesis version of Mortal Kombat shipped with toned-down violence to meet Sega’s MA-13 rating. Entering the code A-B-A-C-A-B-B (which spells “ABACABB,” referencing the band Genesis) on the start screen unlocked the full arcade gore and raised the rating to MA-17.

Why is Mortal Kombat spelled with a K?

The development team struggled to name the game for six months. Pinball designer Steve Ritchie saw someone had written “Kombat” on a whiteboard (with the C crossed out and replaced with K) and suggested “Mortal Kombat.” The deliberate misspelling became a franchise trademark, with K frequently replacing hard C sounds throughout the series.

What are Kombat Kodes?

Six-symbol codes entered at the versus screen in two-player Mortal Kombat 3 matches. Each player enters three symbols using attack buttons. The codes modify gameplay (no power bars, unlimited run, dark kombat), fight hidden characters, or display messages. Example: 642-468 launches the Galaga mini-game.

How many copies has Mortal Kombat sold?

The franchise has sold over 100 million copies as of 2025. Sales milestones: 6 million (1994), 26 million (2007), 30 million (2012), 79 million (2022).

Did Ed Boon really voice Scorpion for 30 years?

Yes. Boon recorded Scorpion’s “Get over here!” yell in 1992 during filming, using his own voice. He has continued voicing the character in every Mortal Kombat game since. The Guinness Book of World Records recognized him in 2010 as the “longest-serving video game voice actor” for this single role.

View Sources

- Boon, Ed and John Tobias. Mortal Kombat Development History. Various interviews, 1992-2025.

- Video Game Canon. “Bite-Sized Game History: Celebrating 30 Years of Mortal Kombat with Ed Boon and John Tobias.” October 22, 2022. https://www.videogamecanon.com/adventurelog/bite-sized-game-history-celebrating-30-years-of-mortal-kombat-with-ed-boon-and-john-tobias/

- Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. “Ed Boon, Chief Creative Officer, NetherRealm Studios.” Special Awards profile. https://www.interactive.org/special_awards/details.asp?idSpecialAwards=42

- Wikipedia. “Mortal Kombat (1992 video game).” Accessed November 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortal_Kombat_(1992_video_game)

- Wikipedia. “Controversies surrounding Mortal Kombat.” Accessed November 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Controversies_surrounding_Mortal_Kombat

- Mental Floss. “‘Finish Him!’: When ‘Mortal Kombat’ Caused a Moral Panic.” May 30, 2024. https://www.mentalfloss.com/posts/mortal-kombat-controversy-90s

- Bloody Disgusting. “The Controversy of Brutal Violence in ‘Mortal Kombat’ (And How It Changed Games Forever).” November 10, 2022. https://bloody-disgusting.com/video-games/3740147/the-controversy-of-brutal-violence-in-mortal-kombat-and-how-it-changed-games-forever/

- Wikipedia. “Mortal Kombat II.” Accessed November 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortal_Kombat_II

- Fatherly. “35 Years Ago, A Controversial Video Game Didn’t Hit The Way You Think.” June 27, 2023. https://www.fatherly.com/entertainment/mortal-kombat-2-release-date-1993-controversy

- Wikipedia. “Mortal Kombat 3.” Accessed September 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortal_Kombat_III

- Screen Rant. “How Mortal Kombat Introduced The M Rating To Video Games.” September 2, 2021. https://screenrant.com/mortal-kombat-first-m-rated-game-esrb-controversy/

- Craddock, David L. “Kool Stuff[6]: How Video Game Ratings Have Changed Since Mortal Kombat II.” March 18, 2022. https://davidlcraddock.substack.com/p/esrb